Image credit: Museum of American Finance / Flickr

By Jason Zweig and Liz Moyer

Oct. 4, 2014 9:48 a.m. ET

The stunning departure of Bill Gross from Pimco raises important questions for investors.

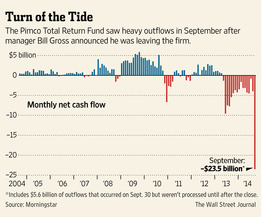

Mr. Gross, the world’s most influential bond manager, left Pacific Investment Management Co. abruptly on Sept. 26, roiling fixed-income markets and sending at least $23 billion scurrying out of Pimco Total Return, the fund he led, which had $222 billion in assets at the end of August. He joined Janus Capital Group, where, starting Monday, he will run the Janus Global Unconstrained Bond Fund, which was launched in May 2014 and has $13 million in assets.

For investors, it is an opportune moment to re-evaluate their bond strategy. Chances are, you don’t need to take urgent action.

Here are answers to five questions that can help you determine what to do—and not to do—if you are a Pimco Total Return investor, if you are worried about rising interest rates, if you are wondering what purpose bonds serve now and if you aren’t sure which kind of bond fund is right for you.

Should you stay or should you go?

The response to this question, says David Merkel of Aleph Investments, a financial-advisory firm in Ellicott City, Md., depends partly on how it will affect your tax bill.

“If I had long-term gains and didn’t want to pay [capital-gains] taxes, and I still believed in Pimco’s process, I’d stay,” says Mr. Merkel, whose firm manages $10 million.

Long-term capital-gains tax rates run from 15% for many middle-class investors up to nearly 24% for the wealthiest ones.

As brilliant as Mr. Gross may be, there is more to Pimco. The firm has about $2 trillion in assets and a solid record in many funds that Mr. Gross—Pimco’s co-founder and now ex-chief investment officer—never touched.

David Snowball, editor of the Mutual Fund Observer website, says Mr. Gross’s departure should ease some of the tension that has been disrupting the firm for months, which could make work easier for the remaining portfolio managers.

Furthermore, Mr. Gross’s colleagues deserve at least some credit for the fund’s outstanding long-term record, Mr. Snowball says. Pimco’s new chief investment officer, Daniel Ivascyn, has outperformed Pimco Total Return at a separate fund, Pimco Income, by an average of 3.6 percentage points annually since the income fund launched in March 2007, according to Chicago-based investment-researcher Morningstar. Pimco Total Return has been taken over by Scott Mather, Mark Kiesel and Mihir Worah, three of the firm’s most senior managers.

If taxes aren’t a concern and you are considering investing in the Janus fund Mr. Gross will lead, be sure you know what you are getting into.

The new fund “could look a lot different than [Pimco] Total Return,” says Sarah Bush, a senior analyst at Morningstar.

Mr. Gross will be free to take risks that weren’t practical in the mammoth fund he led. At Pimco Total Return, if he had found a cheap bond and wanted to put even one-tenth of 1% of the fund into it, that would have meant devoting more than $200 million. Bargain bonds are rarely available in such huge quantities.

The Janus fund, by contrast, is so small that Mr. Gross can concentrate in the best bargains he can find—and he may be free to run it in a more freewheeling manner, Mr. Merkel says.

One other factor to consider: expenses. Mr. Gross’s new fund charges between 0.82% and 1.84%, or $82 to $184 per $10,000 invested, depending on which class of shares an investor owns—compared with Pimco Total Return’s 0.46% to 1.6%. While the Janus fund’s expenses should drop as its assets grow, if you buy shares through a financial adviser you may also have to pay an upfront sales charge of as much as 4.75%.

So if you are risk-averse and hold Pimco Total Return in a taxable account, you should probably stay. If—and this is a big if—you don’t mind taking bigger risks in pursuit of a higher return, then consider following Mr. Gross to Janus. Just remember that greater risk, even in the hands of a manager with an impressive long-term record, doesn’t always result in greater returns.

Among other intermediate-term bond funds rated highly by Morningstar are Dodge & Cox Income, Metropolitan West Total Return Bond, Fidelity Total Bond and Loomis Sayles Investment Grade Bond.

Is it time to ditch active managers—those who pick which bonds to buy and when—for passive index funds?

Staying with Pimco or following Mr. Gross to Janus aren’t the only options. Just as with stock funds that track broad indexes, bond index funds are more likely to generate predictable returns.

At Total Return, Mr. Gross had a 27-year track record of outperforming the bond market by an average of more than one percentage point annually after all expenses. That is some of the best evidence for the argument that an active bond-picker is worth hiring.

But the latest analysis from S&P Dow Jones Indices, a unit of McGraw Hill Financial, finds that over the past five years, 85% of high-yield funds underperformed their benchmark. That is a part of the market where active management should matter greatly, because one risky corporate bond can differ significantly from another.

In emerging-market debt funds, another area where bond-picking skills should be paramount, 64% of funds did worse than the index.

In funds that track the broader bond market, results have been mixed, with 51% of investment-grade funds outperforming the index over the past five years, says Aye Soe, a senior director at S&P Dow Jones Indices.

Meanwhile, you can buy Schwab U.S. Aggregate Bond or Vanguard Total Bond Market, two exchange-traded funds that hold broad swaths of U.S. government and corporate bonds, without trying to outsmart the market. The funds charge 0.06% and 0.08% in annual expenses, respectively—less than the Pimco and Janus funds, and barely one-tenth what the average actively managed bond fund charges, according to the Investment Company Institute, a trade group.

One of the easiest and safest ways you can raise your expected return on bonds is to lower your costs of holding them.

Are you well-positioned for rising interest rates?

Every day, it seems, another investment firm warns clients to “position” themselves for the inevitable rise in interest rates by the Federal Reserve Board.

Before you overhaul your bond portfolio in response, remember that so-called experts have gotten their forecasts of future interest rates profoundly wrong for years.

Since 2010, The Wall Street Journal’s monthly survey of economic forecasters has found that 50 of the nation’s leading economists have, on average, called for interest rates to go up both faster and higher than they did. The only exception was 2013, when the experts finally lowered their interest-rate predictions. Interest rates promptly rose.

The Fed itself has had to revise its forecasts of when rates would rise. In August 2011, the Federal Open Market Committee said it expected to seek “exceptionally low levels” of interest rates “at least through mid-2013.” In January 2012, the Fed changed that to “at least through late 2014.” This year, the Fed has been saying that it will try to keep rates low “for some time”—widely interpreted to mean that rates won’t rise until at least the summer of 2015.

So the Fed already has kept rates lower for longer than anyone—including the Fed—expected. There isn’t any reason to think a rise in rates is any more imminent now.

To be sure, if interest rates do rise, it won’t be painless. Laurence Siegel, who heads the CFA Institute Research Foundation, a financial think tank in Charlottesville, Va., says if past interest-rate cycles are any guide, you should expect the yield on the 10-year Treasury to rise to about 4% or 5% from its current 2.4%. Historically, Mr. Siegel says, that has taken several years.

Based on a measure called “duration,” which shows how sensitive bond prices are to changes in interest rates, you can assume that if rates rise one percentage point, the Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index, the most common benchmark for measuring the fixed-income market, would decline in price by about 5.6%. If rates were to rise two points, the index would fall in price by 11%.

But interest income from newly bought bonds rises as prices on existing securities fall, and that would ease the sting. If interest rates rose 2.5 percentage points over two years, the average investor holding a portfolio tracking the broad bond market would lose almost 5% annually, estimates Mr. Siegel. That is bad, but it isn’t disastrous.

Based on the past 60 years of ups and downs in the market, Mr. Siegel says, bond investors should expect to realize a return of 1.5% to 2% annually over the next three years, given the current 2.3% yield on the Barclays index.

That is the average of all past scenarios—rising, falling and constant interest rates—and is thus a good baseline assumption for how bonds will perform, Mr. Siegel says.

Given that rates can rise further than they can fall from here, he says, prudent investors should shun long-term bonds—maturing in 10 years or more—whose prices will suffer far worse if rates do rise. You also should hold a sizable slug of Treasury inflation-protected securities, which will benefit if inflation jumps unexpectedly.

Do you own bonds for the right reasons?

Many investors own bonds for the income they provide. Unfortunately, they aren’t providing much right now. Don’t let that make you do something crazy.

“This is not a time to try to be reaching for income,” says Mr. Merkel of Aleph Investments. “It’s a time to be reaching for safety.”

If you grew accustomed to 5% to 6% yields from bonds in past years, you have to accept that those days are gone—at least for now. “There’s no easy answer for this low-interest-rate environment,” Mr. Siegel says. “It stinks.”

You could judiciously add a few master limited partnerships—energy-related investments with average dividend yields of about 5%—to your portfolio. Just bear in mind that MLPs fluctuate much more in price than bonds.

Avoid holding MLPs in funds, which can cause complicated tax headaches. Look instead for a specific partnership with desirable assets and a long record of delivering stable income. Simon Lack, managing partner of SL Advisors in Westfield, N.J., says Enterprise Products Partners, MarkWest Energy Partners and Plains All American Pipeline are “pretty attractive” at today’s prices.

Other common “solutions” to the problem of lower yields bring higher risks.

So-called bank-loan, senior-loan or floating-rate funds offer yields of 3% and up. But these funds invest in short-term debt of companies with above-average risk—and lost an average of 30% in 2008.

Emerging-market bond funds invest in debt from developing countries like Brazil and China. They are at least as vulnerable to rising rates as U.S. bond funds are, and more exposed to political risk and fluctuations in the value of the U.S. dollar.

“It’s important to think of bonds as an element of diversification in a portfolio when you get a selloff in the stock market,” says Ms. Bush of Morningstar. “They’re a quiet place in a storm.”

Take the fourth quarter of 2008, when U.S. stocks fell 21.9%—but the Barclays index gained 4.6%. Both figures include price changes and income, from dividends in the case of stocks and coupon payments in the case of bonds. In the first quarter of 2009, as stocks fell 11%, the bond index rose 0.1%.

A stock-market crash is more likely than a sudden, sharp jump in interest rates—and a lot more devastating. Staying invested in bonds is the best way to protect yourself.

Should you invest in an “unconstrained” bond fund?

Among the hottest investments around are unconstrained bond funds. Managers of such funds can invest in any kind of bond (or income-producing asset) they choose, all in search of better returns.

Investment-research firm Lipper estimates that 71% of the more than $70 billion in new money that has poured into taxable bond funds over the past 12 months has gone into alternative or nontraditional strategies.

That number will surely rise now that Mr. Gross is joining the Janus unconstrained fund. But a fund can pursue higher returns only by taking on greater risk.

A manager of an unconstrained bond fund can buy longer-term securities, raising the risk of damage if interest rates rise, or lower-quality bonds, increasing the danger of losses if the borrowers default. Or the manager can acquire securities that aren’t bonds at all—such as shares in business-development companies, which fund startups and other small firms—which can introduce hazards unfamiliar to most fixed-income investors.

Furthermore, such strategies tend to outperform safer bonds in a bull market—but can suddenly suffer when bonds (or stocks) collapse. Their returns are less bond-like and more like those of the stock market, so these funds are less likely to provide the diversification of conventional bond funds in the next stock-market decline, Ms. Bush says.

The ability to go anywhere, says Mr. Siegel of the CFA Institute Research Foundation, gives unconstrained managers an incentive to take unrestrained risks. “To let bond managers buy whatever they want and not be accountable is kind of crazy,” he says. “A lot of them will just take as much risk as possible.”

Source: The Wall Street Journal